The Science of Reading Is More Than Just Phonics

Why phonics is essential—but not enough—to teach reading effectively

The term ‘Science of Reading’ has gained widespread attention in recent years. It often features prominently in professional development for teachers, in classroom resource materials, and, increasingly, in staffroom discussions. This surge of interest in evidence-informed practice is welcome. However, with popularity comes a risk. Complex, nuanced research can quickly become oversimplified or misrepresented.

This brings us to the central myth explored in this blog—a misconception that continues to limit both understanding and implementation:

“The Science of Reading? That’s just phonics.”

Let’s be clear from the outset. The Science of Reading is not, and never has been, just about phonics.

What Is the Science of Reading (SoR)?

The SoR refers to a wide-ranging body of interdisciplinary research drawn from fields such as cognitive science, linguistics, neuroscience, and educational psychology. At its heart, it’s concerned with how children learn to read, why some struggle, and how we can teach more effectively—particularly for children who may be at risk of reading difficulties, such as dyslexia. As Dr Nell Duke succinctly puts it, the SoR is about ‘understanding reading through research’.

Yes, systematic phonics is part of that understanding. But the SoR stretches well beyond it. It also includes the growth of oral language and vocabulary, the importance of reading fluency, and the strategies that support comprehension. It recognises the role of background knowledge, cognitive processes like attention and memory, and the essential influence of motivation and engagement.

To reduce all of this to phonics alone is a bit like describing a full orchestra using only the string section. You may be naming a vital part, but you’re missing the richness of the full ensemble.

Three Key Models that support the Science of Reading

One of the ongoing challenges in education is bridging the gap between research and classroom practice. Too often, research feels distant from the realities of teaching, and practice doesn’t always reflect what we know from the evidence. That’s where these next models come in.

They provide clear, research-informed frameworks that help us make sense of the many strands involved in learning to read. They’re practical, accessible, and grounded in evidence—making them particularly useful for teachers who want to align their instruction with what we know about how children learn to read.

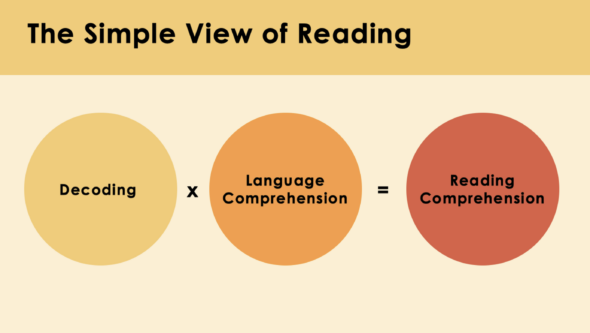

1. The Simple View of Reading (SVR) (Gough & Tunmer, 1986)

This model states that:

Reading Comprehension = Decoding × Language Comprehension

Put simply, children need the ability to decode written words and the ability to understand language in order to make sense of text. Phonics and phonological awareness fit under decoding. But vocabulary, syntax, background knowledge, and inferencing fall under language comprehension. If we focus solely on decoding, we may strengthen one side of the equation while leaving the other underdeveloped.

An analogy I often use to explain the components of skilled reading, and the SVR, comes from Dr Maria Murray. She likens reading comprehension to gold in a treasure chest, locked with two separate locks: one for decoding (D) and one for language comprehension (LC). To access the treasure, both locks must be opened. If either decoding or language comprehension is missing, the chest remains closed—no matter how strong the other key may be.

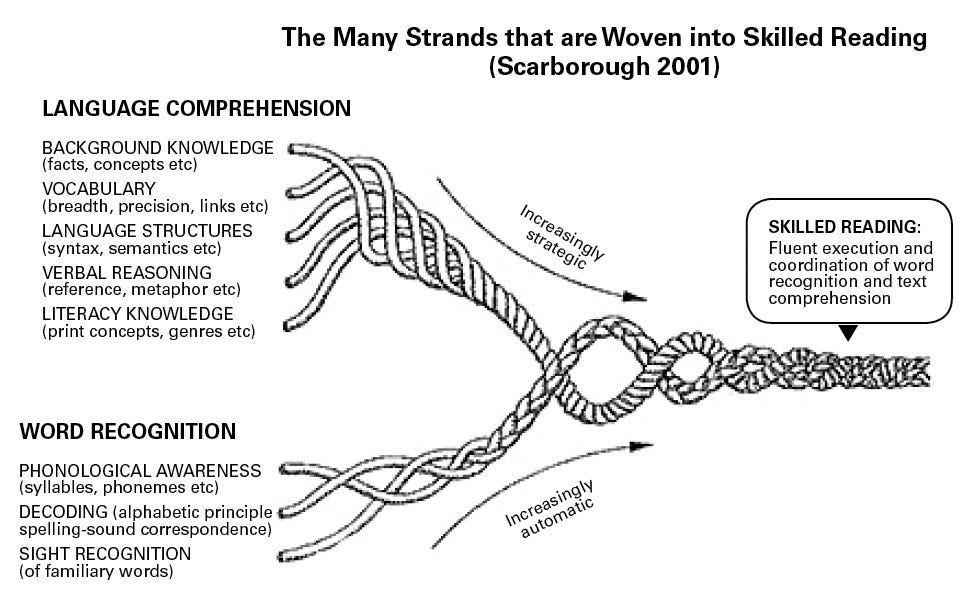

2. Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001)

Scarborough’s Reading Rope helps us visualise how various strands of reading come together over time. It expands upon the SVR model above by breaking down the individual components of word recognition and language comprehension, showing how these elements develop and intertwine as reading becomes more fluent, strategic and automatic.

Like the SVR, it distinguishes between:

Word Recognition: phonological awareness, decoding, sight recognition

Language Comprehension: background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge

As these strands become more automatic and strategic, skilled reading develops. Phonics, in this model, is one strand—important, but not sufficient on its own.

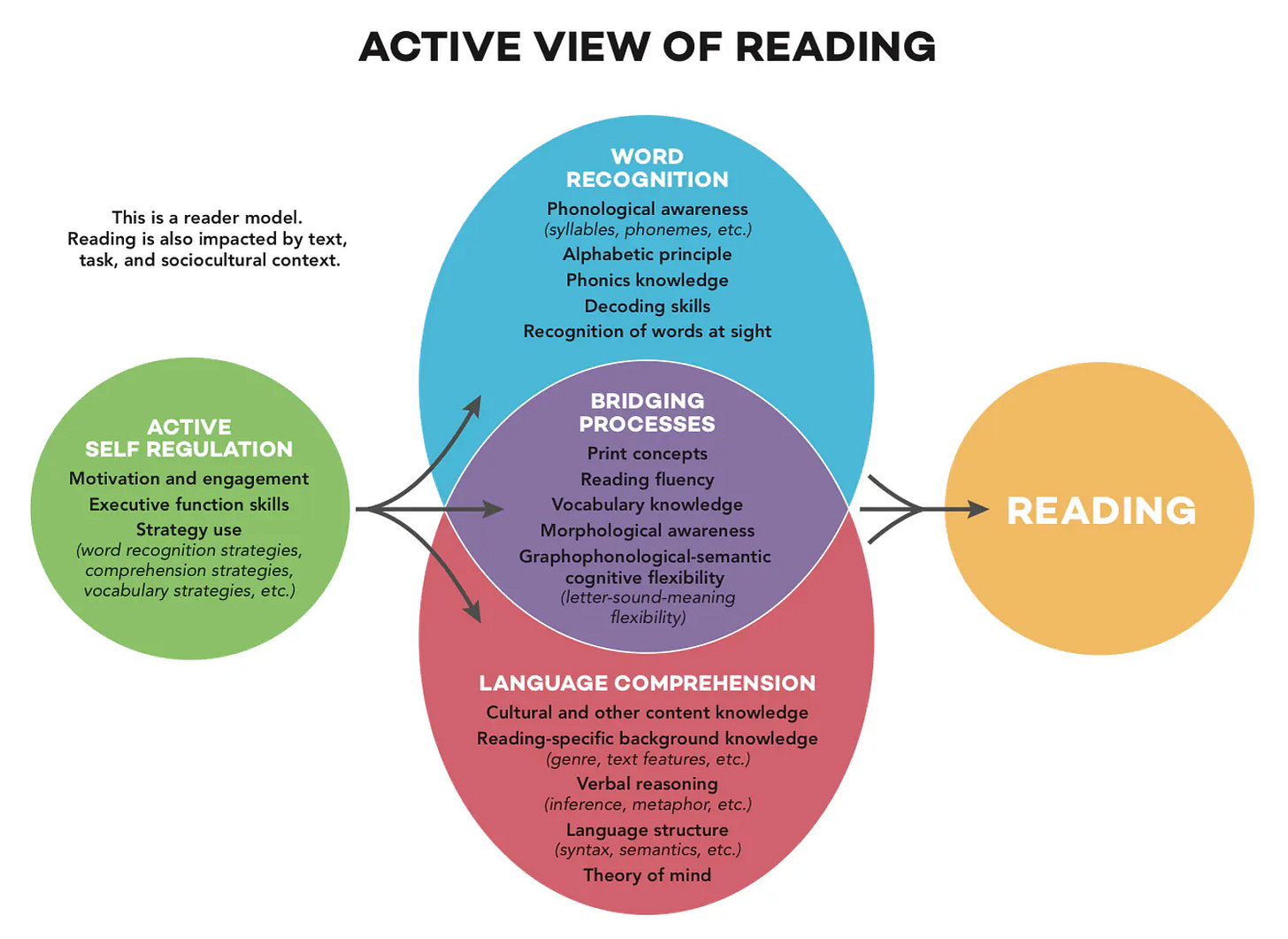

3. The Active View of Reading (Duke & Cartwright, 2021)

This more recent model highlights that reading is not a passive act of recognising words and understanding language—it’s a dynamic, strategic process that requires active engagement from the reader. While the SVR and Scarborough’s Rope offer valuable frameworks for understanding the role of decoding and language comprehension, the Active View expands this picture by including the role of executive functioning, including skills like attention, self-regulation, and working memory.

These are the mental processes that help children stay focused, monitor their understanding, adjust strategies, and persevere through challenging texts. Without them, even children who can decode fluently and understand spoken language may struggle to read with purpose or maintain meaning across longer or more complex texts.

By highlighting the roles of executive functioning and motivation, this model reinforces that skilled reading is not just about recognising words, but about thinking actively and purposefully while reading.

Beyond Decoding

Being able to decode words is a vital foundation for reading, but it’s only one part of a much larger process. Once a child can successfully sound out a word, they still need to understand what that word means, how it functions in a sentence, and how it connects to the overall meaning of the text. Decoding gives them access to the words but not necessarily to the ideas behind them.

Take, for example, a child who reads the sentence: ‘The elephant trudged across the savannah in search of water.’ They may decode every word with ease, but still miss the meaning if they don’t know what an elephant is, where a savannah might be found, or why the search for water matters. Similarly, a child might decode the term ‘evaporation’ in a science text, but without background knowledge or vocabulary instruction, the word carries little weight. This is where language development, background knowledge, and comprehension become essential. Vocabulary, syntax, inference-making, and content knowledge all work together to help children build layers of meaning from print.

If we take the SoR seriously, then our teaching must reflect its full scope. The SVR reminds us that both decoding and language comprehension are essential to skilled reading. Scarborough’s Reading Rope builds on this by unpacking the many strands that contribute to each domain and the Active View pushes the conversation further, highlighting that reading is not just a cognitive task but also a motivational and strategic one, shaped by engagement, attention, and self-regulation.

Taken together, these models give us a clear message: instruction cannot be one-dimensional. It must be broad, coherent, and responsive. That means supporting the development of phonemic awareness and sound-symbol knowledge while also nurturing oral language, vocabulary, and comprehension. It means building fluency alongside curiosity, and fostering the kinds of reading experiences that help children not just decode, but understand, reflect, and connect with text.

So Why Does Phonics Get So Much Attention?

It’s no surprise that phonics often dominates conversations about the SoR. In contexts like the United States, phonics was sidelined for decades. Whole language and balanced literacy approaches were widely adopted, often encouraging children to guess words from pictures, rely on context clues, or memorise word shapes instead of learning how to decode using the alphabetic principle. For some learners, particularly those with dyslexia, this meant being denied access to the crucial skills they needed to read independently. They were never explicitly taught how the written code works. The rise of the SoR movement in the US has brought with it a renewed emphasis on systematic, explicit phonics instruction. In many cases, it has prompted large-scale curriculum changes, new legislation, and widespread professional debate.

In Ireland, the story is somewhat different. While classroom practices may vary, phonics has long held a consistent and recognised place in early literacy instruction here. It is embedded in our national curriculum and supported by key policy documents. Most teachers here are familiar with its importance in helping children develop decoding skills. As such, the conversation in Ireland isn’t about reintroducing phonics, but about how to integrate it meaningfully within a broader model of reading instruction—one that reflects the full complexity of what it means to learn to read.

Avoiding the ‘Narrow View of Reading’

Getting the SoR right is essential because when it's reduced to phonics alone, we distort both the research and the complexities of the reading process. Getting it right also means recognising that not all reading difficulties are about decoding. Many children can read words accurately but still struggle to make sense of what they’re reading due to gaps in vocabulary, language comprehension, or background knowledge. If we concentrate too narrowly on phonics, we risk overlooking those learners entirely.

There’s also a reputational risk. When the SoR is reduced to phonics alone—or worse, turned into a marketing label or educational buzzword—it becomes easy for critics to dismiss it as narrow, rigid, or prescriptive. This misrepresentation not only oversimplifies the research but also undermines the credibility of a movement grounded in decades of serious, interdisciplinary study. In the US, the SoR movement has gained momentum as a response to long-standing neglect of phonics instruction.

However, the conversation there has often swung between extremes, from whole language to balanced literacy to a renewed, and sometimes overly narrow, emphasis on decoding. While Ireland hasn’t experienced such pendulum swings, we are not untouched by international influences. Teachers here remain rightly cautious. They understand that meaningful, lasting change doesn’t come from extremes, but from steady, research-informed practice rooted in the realities of the classroom and the needs of the children in front of them.

A narrow view can also lead to narrow solutions—often packaged as quick fixes or products that promise clarity but rarely reflect the full research base. This reductive thinking not only short-changes children, but it also risks oversimplifying the professional role of the teacher. Teaching reading requires more than delivering a script or ticking off components; it involves thoughtful decision-making, responsiveness, and an understanding of how language and reading develop over time.

Avoiding a narrow view of reading means embracing the complexity of the process, staying grounded in research, and trusting in the professional expertise that allows teachers to apply that research in meaningful and responsive ways.

SoR Buyer Beware!

As awareness of the SoR has grown, so too has the market for materials and programmes claiming to be ‘Science of Reading-aligned.’ While some are grounded in solid research, others are more opportunistic. As Dr Holly Lane puts it, some products are little more than ‘snake oil,’ trading on the term without truly reflecting the depth or breadth of the evidence base.

That’s why we need to approach programmes and resources with a critical lens, considering not just what they claim, but how well they align with what the full body of reading research actually tells us about how children learn to read. While it’s heartening to see such enthusiasm for research-informed teaching, this enthusiasm needs to be matched with discernment. The SoR is a robust and evolving body of research—not a brand.

Final Thought

The research tells us that reading is not a single skill but a complex interplay of language, knowledge, cognition, and motivation. It is built over time, through purposeful, evidence-based instruction and meaningful engagement.

Phonics is a vital part of that picture. But it’s only one part. Teaching reading well means recognising the full range of what children bring to the process and what they need from us in return. It means going beyond accuracy to foster understanding, confidence, and curiosity.

So yes, let’s teach phonics—and let’s do it well.

But let’s not mistake it for the whole story. The SoR has never been just about phonics. We teach children to read not just to decode, but to understand, to think, to question, and to enjoy. If comprehension is not the end goal, we’ve misunderstood the very purpose of reading, and misrepresented the research that should be guiding our practice.

This post is part of Misconception May—a series confronting common myths in literacy education. Stay tuned for more myth-busting insights this month and if there’s a reading myth you’ve encountered—or questioned—I’d love to hear it.

Subscribe, share, and join the conversation in the comments box below.

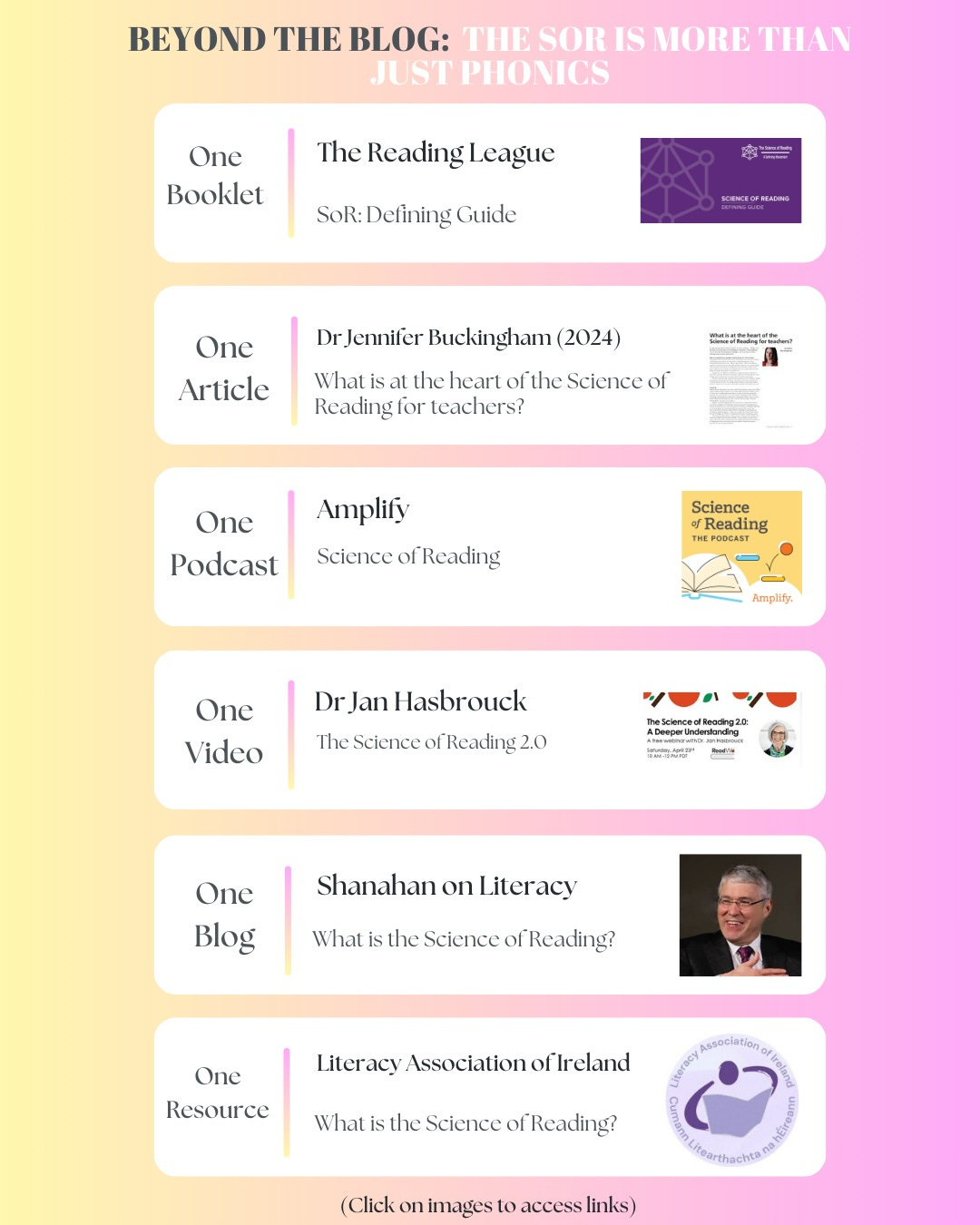

Click on the image below to access clickable links to articles, podcasts, videos, etc relating to this topic.

That’s a really interesting question! Thank you for raising it. I wonder if you're referring to oral reading fluency, which is often discussed as a key bridge between decoding and comprehension in reading development. If so, then yes, there is a strong research base supporting the importance of reading aloud with expression, accuracy, and appropriate pace, particularly through repeated reading and approaches like Readers Theatre, which can build fluency in engaging and purposeful ways. Reading fluency plays a critical role in freeing up cognitive resources for comprehension.

That said, apologies if I’ve misinterpreted your query!

I'm curious, is there reading research that addresses reading out loud to others as a developmental stage, regardless of age groups?